At the right you see a fossilized snail shell found in southwestern Mississippi. Based on its similarity with pictures in a fossil field guide, a good bet is that it's Platyostoma of Silurian or Devonian age, which means it may have lived ±360-440 million years ago. It was found in gravel in the bottom of a deep ravine. That makes sense because geology books inform that most of the gravel in southwestern Mississippi was washed from atop the "Nashville Dome" as it rose, and much of the fossil-bearing rock above the Nashville Dome was of Silurian and Devonian age.

At the right you see a fossilized snail shell found in southwestern Mississippi. Based on its similarity with pictures in a fossil field guide, a good bet is that it's Platyostoma of Silurian or Devonian age, which means it may have lived ±360-440 million years ago. It was found in gravel in the bottom of a deep ravine. That makes sense because geology books inform that most of the gravel in southwestern Mississippi was washed from atop the "Nashville Dome" as it rose, and much of the fossil-bearing rock above the Nashville Dome was of Silurian and Devonian age.

If you're a rank amateur in these matters, probably words like Silurian, and concepts like the Nashville Dome, and gravel washing from atop the rising Dome, are very foreign for you. However, maybe you glimpse the fun you can have by mastering these and a few other simple words and concepts. Just think: You take a walk, spot a fossil, figure out that it probably lived around 400 million years ago, and then have something worth having and showing others. All you have to do is to find it, study it, and have it...

Fossils very often are easy to find. At the right, a trilobite turned up inside a cracked-open chert pebble in a gravel pit in southern Mississippi. Trilobite species dominated the world's oceans around 500 million years ago -- back when plants and animals hadn't yet appeared on dry land. However, all trilobite species went extinct around 252 million years ago. Therefore, the owner of that cracked-open pebble now has what's left of a kind of life that once was very important, but now doesn't exist at all. It's kind of mind-boggling.

HOW DO FOSSILS FORM?

Here's a typical way many but not all fossils are formed:

When a plant or animal dies in the wild, usually it decays and essentially disappears. However, sometimes dead organisms are covered with sediment, such as with mud during a flood or when aquatic organisms settle to the water's bottom, or maybe by ash during a volcanic eruption. For example, the fossil shells at the left were deposited during the Cretaceous Period, about 100 million years ago, in a formation now known as the Del Rio Clay, outcropping in southwestern Texas. It's easy to see that back then mud simply settled around the shells, producing today's shell-rich mudrock.

Organisms thus encased in mineral material don't decay in the usual way, if only because of lack of oxygen. Over the following millions of years minerals in the surrounded material seep into the organism's body, gradually replacing the tissue. The body's more fragile constituents such as protein and carbohydrates break down and are largely or completely removed, perhaps dissolved in water, which flows away, leaving behind a fossil. This kind of fossilization is referred to as permineralization or petrification. The above picture shows fossilized wood from Mississippi.

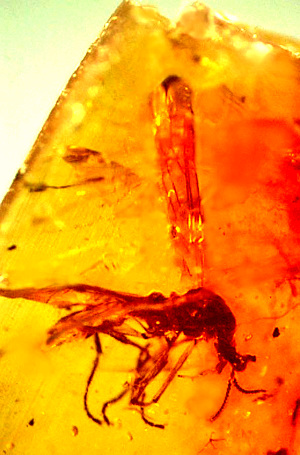

100 million year old Cascoplecia "unicorn fly" fossilized in amber from Burma; image courtesy of Oregon State University.

100 million year old Cascoplecia "unicorn fly" fossilized in amber from Burma; image courtesy of Oregon State University.Permineralization or petrification is just one way fossils can form. At the left you see a kind fly that lived 100 million years ago, fossilized in amber from Myanmar. Amber starts out as sticky resin oozing from a wound in a pine tree trunk. Organisms get trapped in and surrounded by the resin, which then is fossilized into rock. This kind of fossilization is referred to as unaltered preservation.

Besides permineralization/ petrification, and unaltered preservation, other kinds of fossilization include replacement, in which original shell or bone dissolves away and is replaced by a different mineral, as when calcite in shell is replaced by quartz. Then there's carbonization or coalification, when the organism dies and most of the elements in its body are removed, but the carbon remains. During recrystallization, minerals in original shell or bone change into a more stable and longer enduring form of the same mineral, as when aragonite recrystallizes into calcite. Chemically, both aragonite and calcite are calcium carbonate, just different forms.

Dinosaur tracks in Utah; image courtesy of Fred & Diana Adams

Dinosaur tracks in Utah; image courtesy of Fred & Diana AdamsThen there are trace fossils, like those shown at the right, which are not fossilized organisms but rather remnants of the activities of ancient organisms. Trace fossils include footprints, trails, burrows, feeding marks, and resting marks.

HOW OLD IS THAT FOSSIL?

Finding a fossil is much more interesting if you know when the fossilized organism lived. Also, if you know the age of the rock in which you're hunting fossils, you'll have a much better idea of what kinds of fossils to look for.

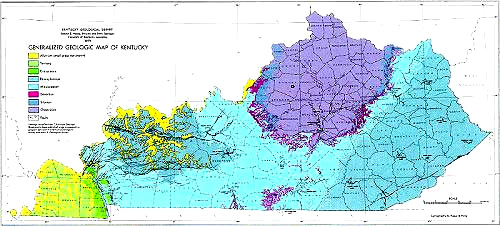

For example, on the above map, if you're in the center of the purple region in the northern part of the state of Kentucky, you'll know better than to look for dinosaur bones. That's because the purple area designates Ordovician bedrock deposited around 450 million years ago, and that was long, long before dinosaurs evolved.

By saying that the purple area represents bedrock that's "Ordovician" in age, we're using the fact that the Earth's geological history is divided into several "periods," of which the Ordovidian is one. When you encounter a period name for which you don't know the age, or what the world was like back then, it's easy to look it up. For example, you might look up the Ordovician on our Geological Time Scale Page.

On that page, not only can the dates be determined, but we learn that during the Ordovician Period the first vertebrates appeared (jawless fishes), and that the seas were dominated by trilobites, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, graptolites, nautiloid cephalopods and marine algae. No land-living plants and animals had yet arisen.

Once you get the hang of finding fossils and using geology maps it's great fun to travel to where rocks of ages different from that of your local bedrock occur, for those rocks may contain different kinds of fossils. For example, leaving the Ordovician rocks in north-central Kentucky to explore the rock in southwestern Kentucky, you might find the crinoid stems at the right. They're ±345 to 310 million years old.

PSEUDOFOSSILS

Sometimes you find things that look like fossils but they aren't. A good guess is that the picture at the right shows fossilized tunnels made by worms burrowing through mud. However, it's hard to say. They're not fossilized tree roots because the rock is Ordovician limestone from central Kentucky, and we've seen that Ordovician fossils are ±490 to ±443 million years old. Back then, trees hadn't evolved yet!

Sometimes you also find fossilized mud cracks, and ripple marks of the kind made in mud in shallow water. Some concretions look like fossils. In fact, sometimes it's just hard to know what you've found!

FOSSIL IDENTIFICATION ON THE WEB

The University of Kentucky has a special page on fossils.

Check out Pennsylvanian Fossils of Missouri and the Florida Museum's Fossil Identification Services.

The EarthSci.Org website has an Identifying Fossils by Shape page.

The Digital Atlas of Ancient Life website offers a free Digital Atlas of Ancient Life App, plus several Digital Atlases for the identification of fossils in certain parts of the US.

In the UK the Natural History Museum offers a Free Fossil Explorer app for the UK.

You can learn what life on Earth was like during the various periods of Earth's history, at Berkeley University's Web Geological Time Machine. For example, on that page's Geological Time Scale, you can click on "Ordovician" to read about life on Earth at that time, and see a picture of some of some Ordovician sea-life.