SONG SPARROW, Melospiza melodia, image by Bea Laporte, Ontario, Canada

SONG SPARROW, Melospiza melodia, image by Bea Laporte, Ontario, CanadaBack when people chopped the heads off their homegrown chickens before plucking, frying, and eating them, something was commonly known that nowadays most of us haven't heard of. That is, when a chicken's head is axed off and the body is flopping around on the ground, the chicken still squawks. Moreover, the sound doesn't come from the chicken's severed head. It issues from the body.

We tend to think that birdsong is whistling, and we know that when we whistle, the sound is made in our mouths. The headless-chicken story is enough to prove that birdsong is something other than mere whistling. In fact, birds have a song-making organ that other animals, including humans, do not, and it's called the syrinx, pronounced SEE-ruhngks.

With humans and most other higher animals, including birds, when air enters the nostrils and mouth it flows into a tube called the trachea, which leads to the lungs. Like humans, birds possess two lungs. Where the trachea forks, with each branch leading toward one lung, that's where the bird's syrinx is located.

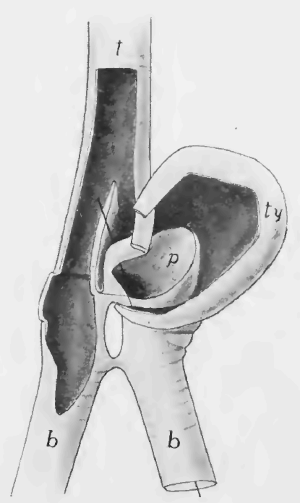

Syrinx of Canvasback Duck; from JS Kingsley, Comparative anatomy of vertebrates. Philadelphia, P.Blakiston's son & co. 1912

Syrinx of Canvasback Duck; from JS Kingsley, Comparative anatomy of vertebrates. Philadelphia, P.Blakiston's son & co. 1912As the drawing at the left shows, the syrinx is shaped like an upside-down, hollow Y, with a kind of projection where the tube forks into bronchial tubes. The projection varies greatly in appearance among the species. In the picture, t at the top is the tympanum, a circular, elastic membrane at the bottom of the trachea, serving as a "vocal chord." At the drawing's bottom, each b is a bronchial tube leading to one of two lungs. The ty is a bulging extension of the tympanum, and the p inside the tympanum's bulge is the pessulus, a delicate bar of cartilage that vibrates, affecting the sound's quality.

Therefore, the syrinx isn't just one gland or organ, but rather a collection of modifications found where the bird's windpipe branches into two bronchial tubes. When singing, the bird tightens its syrinx muscles so that air moving through the syrinx is squeezed, causing the membranes and pessulus to vibrate, making a sound. The bird has wonderful control over these parts, so it can produce a variety of sounds.

Despite being of such simple construction, syrinxes are unbelievably efficient sound-makers. When humans speak, we utilize only about two percent of the air passing our vocal cords. A syrinx uses nearly all the air passing through it.

Since birds make such a huge variety of sounds -- mere occasional grunts and hisses in Mute Swans and Turkey Vultures to brilliant serenades by Mockingbirds and Nightingales -- it's clear that some syrinxes are more developed than others.