It's hard to imagine that the humble little Ground Dove at the right, photographed beneath a backyard hedge in Florida by Michael Suttkus, has anything to do with dinosaurs, but it does.

It's hard to imagine that the humble little Ground Dove at the right, photographed beneath a backyard hedge in Florida by Michael Suttkus, has anything to do with dinosaurs, but it does.

That's because birds evolved from reptiles. This became apparent as early as 1860, when near Solnhofen, Germany one of the world's most famous fossils was discovered in rock strata deposited during the Late Jurassic around 150 million years ago. The fossil was of Archaeopteryx lithographica, which as the image below shows was a species as much reptile as it was bird.

Archaeopteryx lithographica fossil in Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna; image courtesy of Wolfgang Sauber and Wikimedia Commons

Archaeopteryx lithographica fossil in Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna; image courtesy of Wolfgang Sauber and Wikimedia CommonsLike modern birds, Archaeopteryx bore feathers along its arms and tail, but like reptiles, it bore teeth and a long, bony tail. Bones in Archaeopteryx's hands, shoulder girdles, pelvis and feet were distinct, as in reptiles, not fused and reduced as in living birds.

HOW ARE BIRDS ADVANCED OVER REPTILES?

If you think that "flight" first appeared among birds, you're forgetting about pterosaurs, which were reptiles living about 215 million years ago, well before Archaeopteryx. With wingspans of up to 36 feet (11m), pterosaurs flew very well.

If you say "birds were the first animals able to keep their body temperature warm when the air got cold," then you're forgetting that certain dinosaurs are thought to have been warm blooded. Neither is "eggs" a bird invention, because reptiles also lay very serviceable dry-land eggs.

At this point we're left with "feathers." However, fossils show us that many small, reptilian "theropods" probably evolved the first feathers. Theropods were carnivorous dinosaurs who ran around on oversized hind legs. Remove a chicken's feathers and give it a short tail, add teeth to the beak, and you have something close to a theropod. Add teeth and short tail to the "Naked-neck" hen at the right -- a breed common in the tropics because it thrives in the heat -- you'd have something looking pretty close to a theropod.

FEATHERS AND SCALES

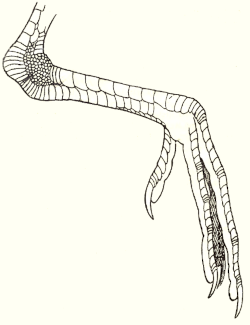

One way to convince ourselves of the closeness of birds to reptiles is by looking at a bird's leg, such as that of the Purple Gallinule, whose leg and foot "scalation" is shown in the public domain drawing at the right. That's from a work by WR Ogilvie published in 1921.

Scaly bird legs and feet look very similar to legs and feet on reptiles such as lizards. This is because genetic information for making a feather is much the same as for making a scale, just with a little extra information thrown in. Well, it's the same with mammalian hairs; Hairs and feathers are "homologous skin appendages," as the experts say, produced by genes sharing "identical molecular signatures" with genes producing reptilian scales. Nature didn't "invent" feathers and hairs all at once, with birds and mammals, but rather played around a bit with pre-existing reptilian scales.

Therefore, in an evolutionary sense, the dawning of the class of birds was, compared to other epoch-making advancements such as the amphibian's emergence from fish, "no big deal." However, in a way, this makes birding even more enchanting.

For, in a real sense, when we observe birds, we're doing something awfully close to "dinosaur watching!"