photo by Laura Maskell

photo by Laura Maskell photo by Bea Laporte

photo by Bea LaporteAbove you see a male Red-winged Blackbird, Agelaius phoeniceus. At the left is an adult female Red-winged Blackbird, and at the right, that's a juvenile Red-winged Blackbird. It's the same species, but with three very different-looking plumages. This matter of plumage change is something interesting to think about.

First of all, consider the matter that it's often the case -- as with the Red-winged Blackbird -- that males of the species often bear colorful and easy-to-see plumages, while females and young are drab. Females and young often display colors and patterns that amount to nothing less than camouflage. Being camouflaged can be helpful when you're a female sitting on a nest, or a fledgling just learning how to survive and developing good flying skills. The world is full of predators who eat their share of egg-incubating moms, and inexperienced young.

It's harder to understand why most, but not all, bird species have evolved so that males are so colorful or ornamented, like the Painted Bunting, Passerina ciris, at the right. Several reasons are possible, depending on the species, and they are discussed in a freely downloadable Scientific American article. One good answer is that females are likely to be in short supply because of the extra work of incubation and chick rearing, so males must compete with other males for a chance to mate with them, and any available females are likely to "best looking" males. That makes a little sense, in that when a male bird's plumage is bright, shiny and neatly preened, probably it means that he's healthy and alert. And if he's brightly colored, then he's certainly quick enough to dodge all those predators who so easily see him.

MOLTING

Periodically birds replace all or most of their old feathers during the process known as molting. Typically, birds keep their feathers for a year, with molting taking place in late summer, after nesting. Sometimes extra molts also occur in early spring, converting somber winter camouflage plumage to brightly colored ones appropriate for courtship rituals.

These plumage changes can be confusing to us birders trying to identify what we see. We grow used to seeing a bird look one way, then later it looks very different, and many field guides don't portray all the plumages! The drawing at the left shows how the same Willet may look, depending on whether it's winter or summer. Willets, Tringa semipalmata, are common wading birds along the US coasts and inland during the summer in the western US, and overwinter as far south as South America.

These plumage changes can be confusing to us birders trying to identify what we see. We grow used to seeing a bird look one way, then later it looks very different, and many field guides don't portray all the plumages! The drawing at the left shows how the same Willet may look, depending on whether it's winter or summer. Willets, Tringa semipalmata, are common wading birds along the US coasts and inland during the summer in the western US, and overwinter as far south as South America.

Many variations on the molting theme exist. Some bird species -- ducks, swans, grebes, pelicans and auks -- are "synchronous molters," meaning that they change their feathers all at once in a period as short as two weeks. Of course, during their featherless time they can't fly; They simply must hide from their predators.

Most bird species, however, molt over a longer period of time, there being a period when old feathers, often drably colored, mingle with brightly colored, newly emerged feathers, as seen on the male Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea, shown at the right. Indigo Buntings, nesting throughout much of eastern and central North America, and overwintering in much of southern Mexico and Central America, undergo an unusually complex molt, diagrammed below:

Note that the diagram begins at the left with a hypothetical baby Indigo Bunting hatching in April, then maybe in mid June the baby's "juvenal" plumage changes to the "formative," which lasts until around the New Year, when the "1st alternate" appears. Around August of the bird's second year, the "basic" plumage is acquired, then maybe in mid-December of the second year the "alternate" plumage appears. But, what do these terms mean?

MOLT TERMINOLOGY

Both the above colorful diagram and its caption suggest the situation. Here are two points to notice:

- Molting can be more complex than simply a juvenile plumage giving way to an adult plumage, which may or may not be different between males and females, and may or may not have different winter and summer phases.

- Molt terminology isn't "fixed," so some specialists may refer to the "juvenile" plumage, which sometimes is written "juvenal," while others may call it "1st prebasic" or "prejuvenal." Other stages are similarly variously named.

In 2021, the following terms regarding bird plumage and molting seem to be understood by most, or at least many, serious birders:

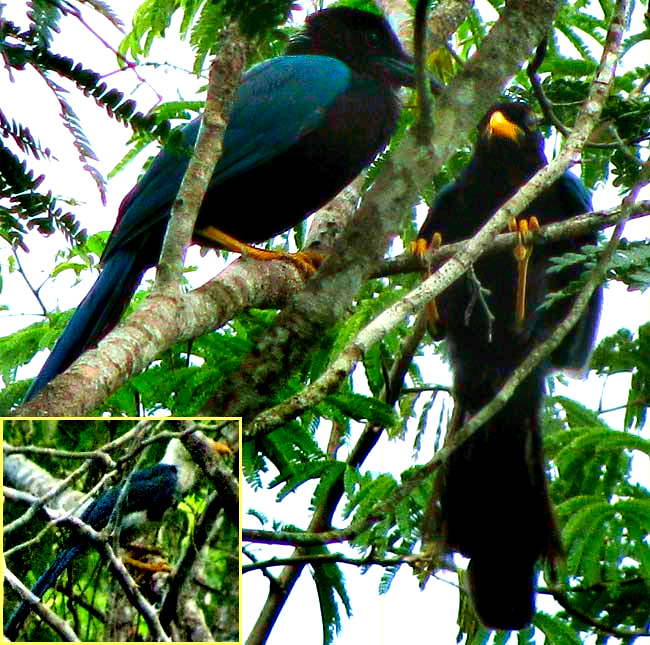

Yucatan Jays, Cissilopha yucatanicus;

Yucatan Jays, Cissilopha yucatanicus; - Natal plumage: on chicks just a few days or weeks old

- Juvenile plumage: on young birds during the summer and early fall of the year in which they hatch

- Subadult plumage: on birds taking several years to mature, especially common in raptors and gulls; basically an adolescent "less distinct" adult plumage, which with times approaches the adult plumage

- Basic plumage: the adult's non-breeding plumage

- Breeding plumage: adult plumage during the courtship period

SEASONAL, NON-MOLT CHANGES

European Starling, Sturnus vulgaris; photo courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife Service

European Starling, Sturnus vulgaris; photo courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife ServiceNot all bird color-changes are caused by molting. For example, the summer breeding plumage of the European Starling, Sturnus vulgaris, shown at the right, is black with iridescent purple and green, but the fall and winter plumage, the basic, is white-speckled, as displayed in the picture. The white speckles are actually the white tips of the basic plumage's black feathers. By the time breeding season arrives, the white tips have worn off, by abrasion. What's left of the black feathers doesn't continue to wear because the pigment melanin, which causes the black color, is resistant to abrasion.

If you're wondering how one year's feathers replace the next year's, you have visited our Feathers Page.